Friday, 14 November 2014

NEW JOHN LEONARD PRESS TITLES AND UPDATE

It's been a wonderful few months At John Leonard Press. Two new titles, created as three-books bound into one (following the US style), have been published, 'A Hunger' by Petra White in August, and 'Keeps' by LK Holt in October. Both were supported by Australia Council Literature Board funding, as our last 12 titles have been in the past four years. 'A Hunger' has been reviewed well by 'Australian Poetry Review' and the 'Sydney Morning Herald' and more are to come. 'Keeps' has just now been sent to reviewers. Both books are produced to JLP's abiding standards of excellence, design and tactile beauty, designed by Sophie Gaur. For more info, go to www.johnleonardpress.com In terms of sales and increased profile for the Press, it was important news in 2015 with the listing of two titles for VCE Literature 2015-2020. Sales have been strong for the two books, Robert Gray's Collected, 'Cumulus', and the anthology of younger Australian poets, ed. John Leonard, 'Young Poets: An Australian Anthology', with numerous schools already having ordered them for the first year. Poets and I will be going into schools to talk about both the Anthology and the writing and publishing of poetry generally. Part of the inspiration here is to ignite the spark in younger writers and readers. These orders followan event the Press organised in early August at the Wheeler Centre in Melbourne, with Australian Poetry, to promote the book and readings to teachers at large. The free event was also open to the public. Kevin Brophy's New & Selected, 'Walking,', published late last year has also sold well and we have just put it into reprint. It was also shortlisted for the 2014 WA Premier's Prize. Both 'Cumulus' and 'Young Poets' have also been reprinted due to their sales. Reviews on Paul Magee's 'Stone Postcard' have also been numerous and positive, including in 'Australian Book Review' and 'Mascara Literary Review'. Links to all reviews are on the Press' website - which has also been recently relaunched. On a personal front, I have also returned to book reviewing, with articles this year for 'Australian Book Review', 'Australian Poetry Journal' and 'Mascara Literary Review', along with having had the opportunity to have written and published a number of articles on poetry, writers and poets for Managing Editor Kent MacCarter at Cordite Poetry Review's 'Guncotton' blog.

Tuesday, 7 October 2014

THE WRITING 2: SARAH HOLLAND-BATT

Jacinta Le Plastrier and Sarah Holland-Batt

The Writing: Sarah Holland-Batt

10 September 2014

Australian poet Sarah Holland-Batt, b. 1982 in Queensland, grew up in Australia and America and also writes fiction and criticism. She was a Fulbright Scholar at New York University where she attained an M.F.A, and is currently a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing and Literary Studies at the Queensland University of Technology and the new poetry editor of Island. Her 2008 book Aria (UQP) won multiple major awards, including the Arts ACT Judith Wright Prize, and was also shortlisted and in the NSW Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry. She has also been a MacDowell Fellow and an Australia Council Literature Resident at the B.R. Whiting Studio in Rome. Her next collection, The Hazards, will be published by UQP in June 2015.

Jacinta Le Plastrier: What is your current poetry project?

Sarah Holland-Batt: I don’t really have poetic projects, per se; my poems come to me one by one, often on fairly unrelated subjects. Lately I’ve been writing a fair bit about visual art; I’ve been particularly interested in works that engage with acts of violence by women, from Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes to contemporary works. Truly clever ekphrastic poems are difficult to do well, although when they do work, they can tilt the axis on which we view the original slightly. I like that challenge. I also like that they demand a long engagement with the canvas or work; I find that sustained act of looking, and of translating the visual into language, pleasurable. I’m also in the early stages of working on a novel, which is a different affair entirely—one I am, for the moment, enjoying. It initially felt like a relief to escape into prose, although its demands are catching up with me now.

JLP: I read that you worked and studied with Sharon Olds on this MS at NYU. Can you tell us a little about that experience? Which also leads to a general question about how much you revise and edit your work with the assistance or feedback of others?

SHB: I studied with several poets I admire enormously at NYU—among them Charles Simic, James Fenton and Yusef Komunyakaa—and I was very lucky to work on the manuscript of my forthcoming book, The Hazards, with Sharon Olds. Sharon is both a stupendous poet and a generous and attentive reader, the rare kind that is able to focus on the poem and poet at hand. I feel very lucky to have spent time with a poet I admire so much. We’re very different kinds of writers, and we didn’t always see eye to eye aesthetically, but I have always loved the kind of intellectual frisson that comes from those disagreements. In general, though, I revise and edit my work almost wholly by myself; I’m not part of any writer’s groups, and I don’t feel the need for much assistance or feedback. My poems go through many, many drafts, and I discard and abandon far more than I publish. It helps that I’m incredibly hard on myself, that I’m essentially animated by doubt. You have to be.

JLP: Why do you think you write poetry? Were there early formative moments which influenced this choice?

SHB: I knew from when I was quite young that I would become an artist of one sort or another. There is a strong artistic bent on the English side of my family; my grandfather was a watercolourist, my father an amateur composer, and our house when I was young was always full of music and my grandfather’s paintings. My early ambition was to be a classical pianist, and I studied that intensively for many years; I do miss the discipline of that now that I’ve given it up. I came to poetry and poetics as a teenager, when I read Wallace Stevens, Eliot and Whitman at high school in Colorado. I understood the music of their poems before I understood the poems themselves, and I responded to it viscerally. Poetry for me has always consequently been a musical undertaking; there’s a mathematical pleasure in the patterns of language for me, just as there is in listening to, or playing, Bach. Intellectually, too, I love the challenge of distilling complex ideas into the small machine of the poem.

JLP: What is your rhythm for writing? I mean, do you work at set times, on set days? Or is it more organic than that for you? And … where do you work?

SHB: I like writing at night while drinking a gin martini. Unfortunately, life isn’t always like a Fitzgerald novel, so sometimes I have to make do with less than perfect circumstances. I prefer writing away from home, in cafes, bars, hotel rooms—there’s something about the anonymity of those public spaces that makes it easier for me to hear myself think. As far as routines go, I don’t believe those people who say that poetry is a job like any other job, and you have to be disciplined: write for four hours in the morning, that sort of thing. That’s absurd. Poetry is art, and art is mercurial, uncooperative and testing. Some days you can do it and others you can’t. I’m not terribly prolific and I prefer it that way. I know that I really mean it when I turn to write a poem.

JLP: How do you personally keep alert for writing poetry?

SHB: I don’t know that I do. I have long fallow periods. Sometimes the best way of writing a poem is to do things that are thoroughly unrelated to writing. I get ideas when I’m reading the morning paper, running, at an art gallery, etc. I never get good ideas when I think, I really ought to sit down and write a poem.

JLP: How consciously do you set out to create and work on a poem? How do they arise for you? And how conscious might be your intentions around technique, form and rhythm, for instance?

SHB: The act of writing a poem is painful and slow for me. I don’t dash off a draft; I eke the poem out line by line, often leaving it unfinished for a few days as I whittle the basic shape of it. My poems are acts of thinking; in them I am often advancing an idea or an argument, and it often takes me days to reach my conclusion. I know that this is different for other poets, who are perhaps more impressionistic and have a more Romantic conception of their own poiesis. For me, writing poetry is a wholly conscious process and my intentions are fairly transparent to me, although they often alter considerably during the writing of the poem. I rarely end up with the poem I set out to write.

JLP: What do you use to write (ie. what tools) and how do think this might influence what is written? For example, do you hand-write drafts and then type them up, or do you work from a computer from a poem’s beginning?

SHB: I like drafting in Moleskine notebooks with a Lamy rollerball pen. I’m a creature of habit about that; I use the same notebooks and pens year in and year out. I prefer to initially write by hand because it forces my thoughts to be more considered; I can only write so fast. By contrast, when I type, my fingers can move at the speed of my brain, which produces a lot of ‘first thought, best thought’ poetry—which, for me, is not particularly considered or interesting. Once I have a rough draft in my notebook, I assemble that on my MacBook. For one, I like to see how long the lines are visually, where the spaces are, etcetera, and I also find I see the poem more objectively if it isn’t in my own hand.

JLP: Can you talk about the role of ‘poetry editor’ and how you find that to be – in context of your new role at Island?

SHB: I’ve only been in the role since May, so it’s still very new. So far, though, it’s been incredibly enjoyable. It’s amazing to be able to put brilliant new poems into print. I love reading submissions and curating an issue, seeing how different poems speak to each other. Of course, it’s also difficult at times, as there are lots of good poems out there and only so much space to work with in each issue; I’m continually confronted with an embarrassment of riches.

JLP: Can you name two or three poets (or particular poems) whose work is important to you, and why?

SHB: Elizabeth Bishop is tremendously important to me. The more I reread her poems, the more moving I find them, despite their surface coolness and control. They skirt and codify the enormous losses Bishop suffered in her life so poignantly. Bishop was unable, or unwilling, to write frankly about Lota (de Macedo Soares) in both life and death, and that devastation comes through in odd and beautiful ways. She’s also a wonderful poet of place. Her Brazil poems have certain postcard-like qualities, immensely visual and painterly, outwardly-focused, supremely clear-eyed.

Another poet who is the inverse of Bishop but who was and is formative for me is Louise Gluck. Gluck is direct where Bishop is elliptical, plain-spoken where Bishop is filigreed, forcefully declarative where Bishop is reticent, but her poems are equally intelligent and controlled. I love her entire oeuvre, but particularly the poems of her middle period (in Ararat and The Wild Iris), where she writes about the death of her father and mortality, respectively. Gluck’s poems are like pieces of Socratic reasoning; unceasingly questioning and anchored in scepticism, they eventually find a through line and snap closed with mousetrap-like logic. She has a fantastic knack of making you feel as though the incontestable truths she articulates are both wholly new and entirely familiar.

* This Q&A commissioned by and produced for Cordite Poetry Review's GUNCOTTON BLOG.

* This Q&A commissioned by and produced for Cordite Poetry Review's GUNCOTTON BLOG.

Monday, 9 June 2014

THE WRITING: BENJAMIN LAIRD

First in a new, occasional series of Q&A interviews at Cordite's GUNCOTTON blog with Australian poets on their writing practice, rhythms and inspirations.

Jacinta Le Plastrier and Benjamin Laird

Jacinta Le Plastrier and Benjamin Laird

The Writing: Benjamin Laird

16 May 2014

Melbourne-based Benjamin Laird writes computer programs and electronic poetry, which he discusses here in the first of a new, occasional blog series looking at the writing practice of contemporary Australian poets. Laird is also undertaking his PhD at RMIT, researching biographical and documentary poetry in programmable media. He is Site Producer for Overland and Cordite Poetry Review. One of his in progress-works is called ‘They have large eyes and can see in all directions’. The reader enters a digital space which appears like a curved diorama, then enlarges to show itself to be like a virtual circular room. The floor and walls are mosaics of text and archived newspaper articles on William Denton, a 19th-century geologist, spiritualist and explorer, whose writing and biography inspires Laird’s poetry here. Some of it hangs and can rotate, in 3-D space, like an Alexander Calder mobile. The reader can zoom in on the many sections to read it. The title comes from a description by Denton’s sons, 19th-century naturalists and collectors, who described lyrebrids (which they were hunting in Victoria) in these terms. The work will be viewable soon at a new website currently being built by Laird.

How do you define electronic poetry? And how did you come to work in this form?

The extremely short answer is where a computer is intrinsic to the material properties of the poem, either where a computer is used to generate poetry, or where a computer needs to be used in order to present the poetry. Even though a lot of poetry is published online and so is digital, it’s not useful to see that poetry as electronic, because it could be just as easily printed out. The definition of electronic poetry also folds out to the culture of those things related to computers.

If we look at Australian-based poets that have worked the area, there is John Tranter with Different Hands (FACP, 1998) where he used software to generate experimental, poetic fiction. There’s Mez Breeze, she writes codework. She has her own form of poetic language, called Mezangelle. And then there is earlier web-based work which began in the 1990s, ‘geniwate’ (Jenny Weight) and, at that time, Komninos, and, currently, Queensland-based Jason Nelson who is very well established internationally. This isn’t a complete list – there are many other Australian poets experimenting with what computers have to offer them. And in a lot of ways the history of the computer also has a parallel history of poets who used computers to write poetry.

It is interesting to see how even the most seemingly benign elements affect how poetry is written now. We are all constraint bound by the media we work in, so the Microsoft Word document – and in Australia its A4 page – that a number of poets are confronted with suddenly becomes a constraint. So people will think about starting to work to margins, expanding what gets printed out. If a journal size is a bit smaller than usual, the poem has to find some compromise on the actual page. When you are working in computational forms, you don’t have the A4 page as a constraint any more, but you have it in the constraints of what comes with the programming language, how you can exploit what a browser can do, or what a desktop machine can do if you are making an app. Phone app poems have constraints of the phone itself. So the actual writing of poetry becomes ‘what can I do within this media?’ – whether it’s in print or whether it is in an electronic form.

A shift in technology drives changes in poetry. The typewriter, for instance, changed poetry, let alone technologies previous to that.

I think it is a very strange thing – there are a number of programmers who are also poets who don’t, say, make digital work and who I think are exceptional … poets like Maged Zaher, an American-based Egyptian poet. He encapsulates the three things I am most interested in: politics, programming as white-collar work and poetry.

These are skills that are meant to be economically productive, and then you turn them into poetry. I started writing electronic poetry five years ago after a long break. It’s been an oscillation between technology and then literature, and then trying to synthesise them.

What is your current poetry project?

I’m writing a collection of biographical electronic poetry works on William Denton, who was a 19th-century geologist, who travelled internationally giving public lectures on evolution and the formation of the world. He was a spiritualist, so he also toured the spiritualist circuits addressing those audiences. He was also a political radical and advocated for women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

One of the main things he was known for was producing, with his wife, a three-volume work called The Soul of Things. (My project is called on The Code of Things.) It was on psychometry; the idea that objects have memories, so if you hold an object, you can see what it has experienced. The project will be a website, progressively developed as part of my PhD with all the works housed here.

He was English-born but lived most of his life in the US. He toured Australia and New Zealand from 1881 and died during a Melbourne Argus expedition to New Guinea.

His sons were collectors of skins and fossils. They had a 19th-century attitude to the environment, which is to collect it. They hunted lyrebirds in Victoria, for example, which triggers subject-matter for one of the work.

The whole project is an attempt, within the six works, to represent William Denton, including his relationship with his eldest sons, and to use poetry in programmable media to create a biography.

Do you think electronic poetry is misunderstood in the literary community by both other poets and readers?

No, I don’t think so. The biggest problem is that there is not a lot of work out there. Ideally, there would be a lot more people writing this kind of poetry so it would be more natural to see it in literary journals. Last year when Overland published an electronic poetry issue it got really great responses by people who read the work and by others inspired by it. One of the challenges of creating this work is, because it’s not seen as frequently, then people who would otherwise like it are not so sure of how technically feasible it is to publish. Likewise, poets inspired to write electronic works find it difficult to know where to start.

Were there early, formative moments which influenced your writing of poetry?

I think it’s a really interesting question for poets to consider. There are many ways to work with language … so the fact that people choose poetry fascinates me because I think it is the most intimate relationship you can have with language. When I was three, I lived with my grandparents for a year. They spoke Tamil, but also spoke English (my family background is Sri Lankan). I went to a local school there (in Malaysia) and nobody spoke English. At least that is how I remember it. Only having one language in order to access the world, where that was no longer useful to me in relation to other people, was a foundational experience in terms of clarifying my idea of what language was.

So it created a sense for me that language was a thing, a material thing, and I guess the next step, beyond-using-language-naturally, was when I began to program. I had a computer quite young and programmed in high school enough to know that we had other forms of language which actually did things to machines. So there’s a sense that poems are like machines, they’re sculptured language, they’re assembled language.

What is your rhythm for writing? Do you work at set times, on set days? Or is it more organic for you? Where do you write?

I don’t have set times or rhythms in terms of working on poetry. I start with a notebook, starting with the initial poem, even if it’s an electronic work, then I will oscillate between writing and designing, assembling and programming across a work. I might also go back to the notebook.

For me, I find creation really interesting when writing a poem – you write the words, then you write it into the space, then you write the time around it. Everything needs to be meaningful in that relationship, the movement, the temporal qualities, the kinetics of the work, the spatial (where it actually occurs on the screen or within the digital space of the poem), and the semantics of the actual language involved. I mostly work at (pointing to) this desk (in doctoral offices at RMIT).

How do you keep alert for writing poetry?

I read poetry, print and electronic, as much as possible. And reading other things too: computer books, literary criticism, computer code, newspapers and corporate copy.

Can you name two or three poets (or particular poems) whose work is important to you?

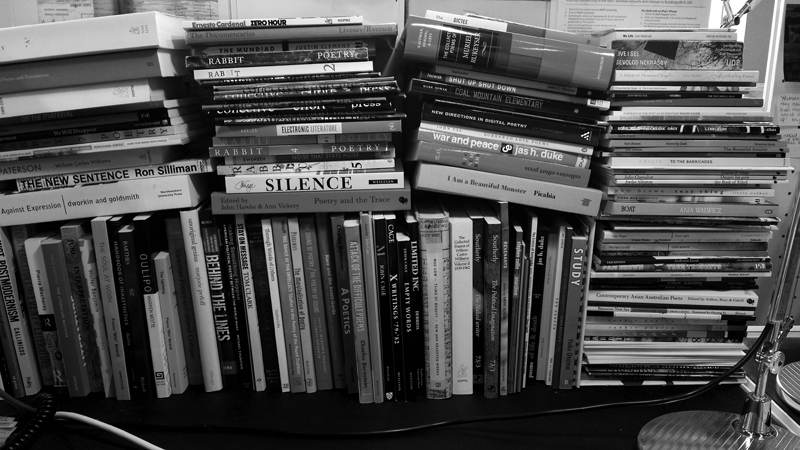

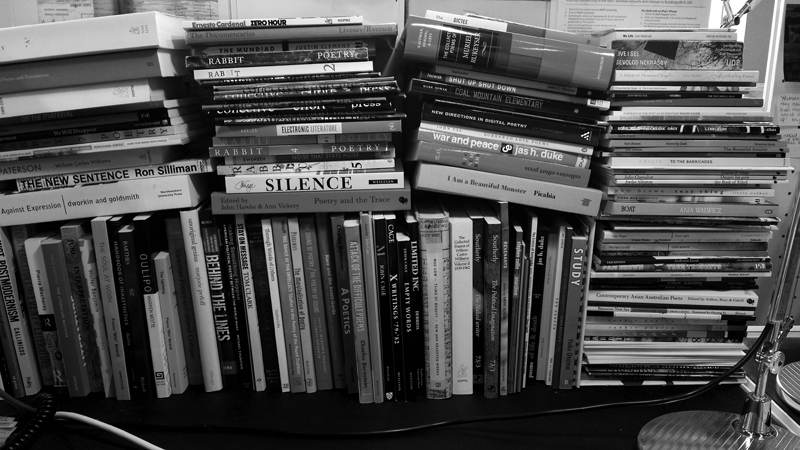

In three poets I’m not even sure I could cover all the kinds of poetry. So I send instead this photo of the current collection of books on my desk. More specifically, though, I’m not sure where I’d be (in terms of poetry) if I hadn’t read Ania Walwicz, TT.O or Pam Brown.

At the moment I’m looking at quite a lot of documentary poetry and so recently read Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead, which is an incredible long poem in so many ways. And Jessica Wilkinson’s Marionette is a fantastic book that intersects the experimental with the biographical.

On the electronic poetry front, the works Nick Montfort and JR Carpenter were very significant when I started mixing code and poetry.

Monday, 31 March 2014

WHEN THEY COME FOR YOU: POETRY THAT RESISTS

Posted 11 March, at Guncotton blog for CORDITE POETRY REVIEW

Jacinta Le Plastrier

Jacinta Le Plastrier

When they Come for You: Poetry that Resists

11 March 2014

Pages: 1 2

‘This machine surrounds hatred and forces it to surrender’ were the words inscribed on the banjo of American folk legend and activist Pete Seeger, who died at 94 in late January 2014. Reading the tributes to Seeger, I was struck by a recurrent theme: his moral courage, which he lived out unrelentingly across a lifetime. Commenting on the ‘not common behaviours’ which made his life exemplary, a New Yorker post by biographer Alec Wilkinson wrote of ‘his insistence on his right to entertain his own conscience’.

That ‘insistence’ began early; Seeger preferring to face jail rather than invoke the Fifth Amendment defense when called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955, and refusing to name personal and political associations. He avoided jail only on appeal in 1962. In October 2011 he was among the leaders of the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ march.

The tributes also led me to think of the ways in which other high-profile figures in popular music – Bob Marley and Bob Dylan – have in the past century harnessed, insisting on their same right, the active, lyrical power of poetic language to express moral and political dissent.

This is one of the reasons for the diminished audience for poetry in the 21st century; its audience, lean as it has often been, has been further subsumed by other arts. Of course, at the same time, the meld of lyric and instrument harks to the days of the lyre, the bard and troubadour, lyric’s origins and tradition.

Yet there is an essence in poetry, where a poem can be a pure or unique instance of language (to use Paul Celan’s thinking), giving it the capability to be a stand-alone language of resistance. It has been often, in the works of accomplished poets, a language of essence, able to name what is essential to the fully lived human experience, and what depraves it.

There are abundant examples. Celan himself – in the words of translator Katherine Washburn, after being earlier a ‘pure poet of the intoxicating line’, and in the steep of the Surrealists – became ‘heir and hostage to the most lacerating of human memories.’ As a Romanian-born Jew, Celan worked in a forced labour camp for 18 months from 1942-1944. Both his parents died in Nazi camps. Just one excerpt here, from his 1952 book, Poppy and Memory:

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night we drink you at noon death is a master from Germany we drink you at sundown and in the morning we drink and we drink you death is a master from Germany his eyes are blue (trans. Michael Hamburger)

And another, from the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, from ‘Victim No. 48’:

He was lying dead on a stone.

They found in his chest the moon and a rose lantern.

They found in his pockets a few coins,

A box of matches and a travel permit.

He had tattoos on his arms.

His mother kissed him

and cried for a year.

Boxthorn tangled in his eyes.

And it was dark…

(trans. Abdullah al-Udhari)

Both poets wrote other poems with dissenting force rising from more opaque and abstracted language. This is a cardinal point: the poetic force is not reliant on a singular poetic or only poetry that has an immediacy or transparency of meaning. It can be present in all kinds of poetry, including those whose language is complex, or difficult to access and decode. In fact, a capacity for ambiguity and subtlety – and an interrogation of the ability to speak at all – might be exactly what is required in such a poem.

This force is pressured by the complexities of linguistic play; pressured by the porous intricacies between poet, poetic voice and subject; and between the poem and the reader. Where it is calculable about political dissent, it can be pressured by multiple, insidious forces which need to be traced. A lucid and intelligent essay on this subject, ‘Poems from Guantanamo: Testimonal Literature and The Politics of Genre’, by Nina Philadelphoff-Puren, is part of the selection by editors Ann Vickery and John Hawke in their 2014 Poetry and the Trace (Puncher & Wattmann). It is worth reading.

The audience for poetry of moral witnessing has not always been, as it is usually today, small. During many socially traumatised times in history, in fact, the ability of poetry to express human conscience has seen it embraced as significant to a massed community.

The poets of these territories and events have also been embraced as public figures whose poetry and project is important to their community of origin: Yannis Ritsos, Pablo Neruda, Anna Akhmatova, Federico Lorca, Nazim Hizmet, Darwish and Miroslav Holub are 20th-century examples. Poets such as W.H. Auden (in poems which include ‘Epitaph on a Tyrant’ and ‘Refugee Blues’) or Wislawa Szymborska (‘Reality Demands’, ‘The End and the Beginning’) exemplify the duty and capacity of a poet to respond to their world, as human community, at large.

Also important about these poets’ contributions is their works’ reinforcement of humanitarian values – their insistence on nobler attributes against a certain era’s atrocities is distilled for the record. The poems are not only for their times. In these cases, the poet is not just a poet, but also an auditor of communal memory. The hook of poetry into the greater communal, in times where a society is embattled and pervaded by the injustices, remains alive.

The communal uptake in recent years of a traditional folk-couplet form, the landay, by Pashtun women in Afghanistan, demonstrates this. An extensive 2013 article inPoetry Magazine relays the story behind the contemporary adoption of this short, oral poetic form –its only rule is syllabic count, a first line of nine, 13 for the second – among Pashtun women living in Taliban strongholds in Afghanistan.

The author, New York poet and Guggenheim Fellow Eliza Grizwold, in her research collected examples of these modern landays on trips beginning in 2012 and interviewed their disseminators. These women create new landays or re-write existing ones, and go on to share them, at the highest personal risk.

Translated by Grizwold, with the assistance of Pashtun speakers and translators, some examples:

Translated by Grizwold, with the assistance of Pashtun speakers and translators, some examples:

You sold me to an old man, father. May God destroy your home, I was your daughter. * I dream I am the president. When I awake, I am the beggar of the world. * The drones have come to the Afghan sky. The mouths of our rockets will answer in reply.

Importantly, the poems are understood to be anonymous and collectively owned; usually, and as a form of protection against retribution, no woman can be held directly responsible for their creation. Many are a condemnation of and resistance to the country’s absorption of an American presence, or a rallying against gendered oppressions. If shared in person, it must be in secret, with landays recited (usually sung, a proscribed practice) privately, woman to woman, or among gatherings of women, including in refugee camps. Grizwold also reported on a secret literary circle, with a telephone hotline, which could be used for the sharing of the poems with those who were unable to attend in person; and to mentor younger women in the form. The landays can also be ribald:

Unlucky you who didn’t come last night,

I took the bed’s hard wood post for a man.

Certainly, as Grizwold comments, the women’s landays ‘frustrate any facile image of a Pashtun woman as nothing but a mute ghost beneath a blue burqa.’

Turning to Australia, there can be no doubt that travesties of human rights prevail here at this time. Topically, there has been the descent into atrocity again with the violent death of Reza Barati and the severe injuries suffered by other asylum-seekers during events on Manus Island this past month.

‘A sheet of paper is to me what the forest is to a man on the run,’ wrote Russian poet, political dissident and labour-camp internee, Andrei Sinyavsky, in his collection of writings, A Voice from the Chorus, made during his imprisonment of nearly seven years. Almost incredibly, it is an observation which might hold acute relevance to the experiences of asylum-seekers detained at this time under Australian Government auspices.

Aside from the refugee-rights issues, there are the indictable inequalities and histories experienced by Australia’s indigenous, poor and marginalised. For the Australian poets who might want to take them up, these ills inevitably mix with the world’s horrors, reminding us that the public resistance of poetry is not bound by a poet’s nationality and place.

Yet there is a troubling issue to be thought through by poets wanting to address the institutional travesties around human rights which prevail in this country. If the poet does not have at least indirect personal association with the impact of an atrocity, then in writing poetry of it, they assume instead the place of the bearing of witness. This can easily come across as helpless (if heartfelt), at least even a little indulgent, hand-wringing. And yet a poem will be a good poem, not because the reader can read the poet’s own experience in it, necessarily, but because of the new ‘thing’ that it makes, or colludes to make, of our immediate world.

This has made me think of what examples there might be of Australian poetry which faces up to the task of addressing such injustices – and of those poems which fail in this.

This species of inferior poem, executed glibly, inanely or just palely, falters for a number of reasons. Often, its inadequacy is due to a blatancy of emotional response that doesn’t impel the reader to a deeper comprehension of what is at stake. Or the poems fail because the poet has begun the task without an insight into why they are writing them, without thinking through why they might have the right to do so – and the densities of that right. Where there is a simplistic conflation between an event of horror and the poet’s assumption of the right – and ability – to speak of it, there goes much of this poetry. This can be the case, whether the horror has been directly/indirectly experienced, or is being ‘witnessed’.

On the other hand, where poems of moral conscience succeed, what they essentially do is remind us, intelligently and movingly, of our own humanity – and potentially too, of whatever obligations (whether civic or private) might subsist for us. Strangely, the test for the worth of such a poem might be that it speaks to our own individuality, not to agendas.

There is a strong precedent of poetry by Australian poets which has been able to ‘bear witness’ and distill communal and emotive undertows of dissent and resistance: A.D. Hope’s ‘Inscription for a War’, Robert Adamson’s ‘Canticle for the Bicentennial Dead’, Robert Harris’s ‘dolekeeping rag’, Bruce Dawe’s ‘Homecoming’, much of Oodjeroo’s oeuvre (including ‘Municipal Gum’) and Kevin Gilbert’s (‘The Soldier’s Reward’); also in a range of subjects in the poetry of Judith Wright.

I also thought of poems whose achievement and timing was endowed by a more solitary, arguably more disturbing, stance: Francis Webb’s ‘End of the Picnic’, with its unsettling and unsettled ending; Dorothy Hewett’s ‘The Hidden Journey’; Vincent Buckley’s ‘Hunger Strike’, on the IRA hunger-strikers, including Bobby Sands (and which was written at a time of vehement anti-IRA sentiment here and abroad); the destabilising tumult of Gwen Harwood’s ‘Night Thoughts: Baby & Demon’.

Poetry of ‘resistance’ cannot always be a galvanisation of communal trending, the audience already captured. In this, poetry at nub is the resisting force – to clichéd thoughts and values (of whatever political bent), to unexamined perceptions of events, histories and the self’s relations to them. Even the concepts of ‘resistance’ and ‘dissent’ cannot be colonised, but remain open to disruption and unpredictability.

Among examples of a conscious nature in more contemporary Australian poems – again, some of these speak in the light of a communal dissent – is Kevin Brophy’s ‘Salt’. From his 2013 volume, Walking,: New & Selected Poems., he addresses here, humanely yet sharply, the boat-refugee issue, and without the flaws of either false conflation or sentiment. Last year’s extended Mundiad collection by Justin Clemens, for all its satirical reflexions and at times uproarious wit, can also be seen, as a commentary on contemporary values, as politically savage. And the poetry of Lionel Fogarty remains idiosyncratic, un-pinnable, disruptive – in its agitating subject matter and its defiance of usual syntactical and grammatical ‘law’.

Tangentially, I also think of Michael Farrell’s 2011 ‘Motherlogue’, with its strange, unhinging enunciation of an apparently indigenous woman’s urban existence and her adaptions, some perverse, some subversively authoritative, to displacement. The poem appears, simultaneously, to be inlaid with inherent and anxious questions about the politic of language and voice, about their ownership, appropriation and disenfranchisements.

Different but still curious questions are also raised in poems such as Emma Lew’s ‘Lesson’ and Iraqi-Australian poet Adeeb Kamal Ad-Deen’s ‘Something Wrong’.

A poem by Alison Croggon, part 3 of a cycle titled ‘Possible Elegies’, is compacted in 47 longish-lines with no stanza breaks. Croggon’s poetry often combines subject matter of an ambitious scale with an ability to reveal its intimate and visceral nature. Her poetic intention, its wreaking of language, is highly conscientious. It addresses love, its imperative co-existent with its frailties and complexity, and the atrocities that would erase it. It also, in a meta-sense for me, offers a possible framework of comprehension to approach other poems that insist on the right to ‘entertain’ one’s conscience, as poet or reader.

The poem is also an inheritor, to my mind, of the injunction that Auden’s ‘The Cave of Making’ set on poetry:

but we shan’t, not since Stalin or Hitler,

trust ourselves ever again: we know that, subjectively,

all is possible.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)